CFK Africa

- Nonprofit

The United Nations (UN) estimates that around the world, over 265 million children are out of school, 20% of these being of primary school age. Forty-seven percent of out-of-school children live in sub-Saharan Africa. According to UN data, between 2010 and 2019, the global primary school completion rates increased from 82% to 85%. In sub-Saharan Africa, the primary completion rate rose from 57% in 2010 to 64% in 2019. COVID-19 has disrupted this progress and sub-Saharan Africa continues to have the highest out-of-school population in the world. Children experiencing poverty are disproportionally deprived of education and learning. In Kenya, over one million school-aged children do not attend or complete school due to poverty, and poverty rates are disproportionately high in the country’s informal settlements. Worldwide, one in eight people live in informal settlements characterized by overcrowding, poor sanitation, minimal economic opportunities, and a lack of access to quality, affordable education. The UN-Habitat estimates that 25% of the global population will live in informal settlements by 2030. Kenya is home to 1,400 informal settlements that house 56% of the country’s urban population. In Kibera, one of Africa's most populated informal settlements, over half of the population is under the age of 15. While youth are critical in catalyzing positive change and supporting development efforts in informal settlements like Kibera, limited opportunities and high unemployment rates often lead to adverse outcomes, including school dropout, substance misuse, teenage pregnancy, and violence.

CFK Africa’s project, the Best Schools Initiative, benefits primary school-aged children (5-12) living in informal settlements in Kenya. Less than half, probably closer to one-quarter, of children living in Kenya’s informal settlements successfully finish primary school. While the Kenyan government began offering free nationwide primary schooling in 2003, the options in informal settlements are limited, sometimes nonexistent, and often low quality. Kibera has nine government schools that can only serve less than a quarter of the community's school-aged population of more than 87,000. The only alternative option is for students to enroll in informal schools, which number about 300 in Kibera alone.

Informal schools are educational institutions that do not meet the government criteria for registration as a school. These schools are often operated by individuals, religious groups, or community organizations, charge restrictive fees, and often provide low-quality education. Additionally, many employ teachers who did not finish their own education and lack appropriate training. In sub-Saharan Africa, 64% of primary school teachers have received minimal training. Due mainly to the growth of these informal schools, the number of children in Kibera who have ever attended school has risen from 15% to 90% over the last 15 years. However, it is important to note that being in school is not the same as learning. Estimates based on surveys conducted by the Kenya Education Staff Institute (KESI) and education researcher Steve Arnold, Ph.D., suggest that 25% to 50% of youth in Kibera do not complete primary school or pass the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education exams. This means that tens of thousands of students each year do not qualify to begin secondary school, leaving them unable to complete their basic education and restricting their access to economic opportunities. The latest World Bank research shows that the productivity of 56% of the world’s children will be less than half of what it could be if they enjoyed complete education and total health. Unfortunately, this learning environment is not only present in Kibera but in informal settlements worldwide, affecting millions of children.

As part of CFK Africa’s Education and Livelihoods programming, the Best Schools Initiative (BSI) leverages its equitable research platform and expertise in participatory development to collect data that informs school-based practices to increase the rate of primary school completion for students in Kibera, where a majority of students do not qualify to begin secondary schooling. The BSI is rooted in private, low-cost, informal schools, which have a variety of structural challenges that CFK Africa is working to address through research and data-driven interventions.

With this project, CFK Africa is moving beyond traditional methods of educational development commonly deployed by NGOs, such as the funding and distribution of individual scholarships, by increasing the capacity of informal schools to improve long-term outcomes for all underserved students in informal settlements. The BSI is not a temporary solution to educational inequality but rather a project focused on addressing the structural challenges facing informal schools.

From 2016 to 2018, the BSI conducted extensive research in Kibera to learn what affects student attendance, retention, and completion at the primary school level. First, the BSI implemented a mixed methodology to collect baseline and experimental data in 64 schools. We interviewed over 1,000 households, 40 school Head Teachers and Directors, and 20 local education NGOs. Combining primary quantitative data from the survey with themes developed from the qualitative interviews, the following emerged as ways to keep kids in school and engaged in learning:

• Schools are run well by their administrators and with accurate records

• Trained teachers with reasonable pay that encourages them to stay the whole year

• Parent or guardian involvement in their child’s education

• Stable and affordable school fees

• Reliable free lunch programs

• Student to textbook ratios that allow every child to see a textbook

• Student access to enjoyable, age-appropriate reading materials

• A reward program to encourage good attendance

• After school and between term classes to keep kids interested in learning

The traits identified are mostly absent in Kibera’s 300 informal schools. There is a gap in education access and transition for children living in informal settlements. Informal schools are being created to bridge that gap; however, they are lacking in the traits that keep students in school and engaged in learning. Additionally, it is unclear which factors most affect student success in primary school or which are scalable. The BSI is designed to change that using a three-phased approach to test, monitor, evaluate, and implement the most impactful and cost-effective best practices for informal schools.

Phase 1: Basic Level - The BSI brings one of these solutions to as many schools as funding allows. This is our current stage.

Phase 2: Discovery Level - With our research partners and donors, we ensure that certain conditions are met at the participating schools over time. This will allow us to collect reliable, comparable data to draw valid conclusions about which solutions are most effective. This is currently in development.

Phase 3: Scaling Level - CFK Africa will disseminate what we have learned to the educational research community, international NGOs, governments, and parastatals or quasi-governmental agencies, hoping that what we learn can end this tragedy of millions of children worldwide not completing their primary education.

- Women & Girls

- Primary school children (ages 5-12)

- Peri-Urban

- Urban

- Poor

- Low-Income

- Minorities & Previously Excluded Populations

- Persons with Disabilities

- Kenya

- Kenya

CFK Africa believes that a community’s problems are best solved by those living there. The organization is rooted in the community and prides itself on its participatory development approach. Based on more than 20 years of experience and strong partnerships with the community, government, public sector, and research partners, CFK's Africa's Community PREFERRED model illustrates how to lead equitable research and sustainable programming that transforms lives and informs policies.

The Best Schools Initiative (BSI) was designed entirely by the local community. Equitable research and community participation drove the development of the BSI and continues to influence the program’s approach. A series of forums were conducted with local community service organizations reaching 500 community residents. We broadly asked the residents, what are the main problems they need help with? The almost unanimous response was an education for primary-aged children and money to start businesses. Community members said their children were not finishing primary school, and they wanted that to change. As we began to explore the barriers to children attending school, interviews were conducted with over 1,000 households, 20 NGOs that had programs in education, 40 school administrators, 15 teachers, and 3 County Education Officers. We asked why kids were not staying in school and what could be done to change that.

Findings indicated that the most significant barriers to quality education included: episodic student attendance, inadequate teacher training, low teacher retention and pay, high student-to-textbook ratios, unreliable feeding programs, lack of parent or guardian involvement, lack of extracurricular activities, lack of classroom facilities encouraging learning and student worth, and unstable, unaffordable school fees.

The "best practices" CFK Africa developed are all solutions proposed during these interviews. We continue to involve the community throughout project development. We regularly bring the administrators of the schools implementing the practices together for feedback sessions and seek their suggestions to improve the program. We bring administrators of schools not participating in the program together regularly for their feedback and suggestions on how to improve the program. We send community volunteers to the schools implementing the practices every two weeks to gather progress data and identify implementation problems.

CFK Africa has been rooted in the Kibera community for over 20 years. In 2021, the organization began conducting baseline surveys and feasibility studies to inform expansion into other informal settlements across Kenya. As we expand, Dr. Steve Arnold, education activist, CFK Africa the Best Schools Initiative (BSI) Co-Founder, and Professor of Religious studies, has collaborated with our leadership team to develop “Theory of Change workshops,” which will help us become effective catalysts for change in the 20+ informal settlements we are expanding into across eight counties. Steve is conducting workshops with CFK Africa staff and will be hosting a theory of change learning group for all stakeholders involved with the BSI. Through these workshops, the CFK Africa Education and Livelihoods team has drafted the following theory of change for the BSI.

On the Nesta Standard of Evidence Scale, we would likely score between a one and a two. We can describe what we do and why it matters. Given the nature of a longitudinal study, it is expected that we will not have completion data until the end of the study. However, due to a multitude of factors, including the complex environment posed by informal settlements, we have not yet been able to capture valid and reliable data, which shows that implementing the practices has caused a positive impact on student primary school completion. The evidence that we are currently using to continuously improve the BSI comes from interviews with school administrators, our own observations when visiting the schools participating in the BSI, and feedback from the Advisory Council. From this evidence, we have mostly learned what is not working and needs either revisions to the practice or discontinuing the school from the program.

Informal settlements are transient, making regular and reliable data collection difficult. In this era of COVID-19, all schools in Kenya were fully closed for an entire year, and only partially open the past two years. Implementing the program and gathering data has been impossible during this time. Adding to the complexity, schools lack tenure and are often destroyed. During our initial year of data collection, of the 24 schools we were working with, eight were destroyed within a year. In addition to the physical structure, the educational environment for schools in informal settlements changes significantly and frequently. School administrators seldom stay more than two years at a school, and students often have two or three different teachers in a school year. Accurate student attendance records are extremely difficult to obtain in informal settlements for numerous reasons, one being that most students change schools once every two years; some may attend three different schools in one year. A recent educational/social project in Kibera spent nearly a million USD to accurately track the 1,500 students they were working with. At the end of the project, they said one of the greatest obstacles they encountered was gathering accurate data on those students.

Implementing a new practice is a complex process for schools, and consistent, full implementation takes varying amounts of time for each school. It's unreasonable to assume that the impact of any of the practices can be seen in one year of a student's schooling. Most practices need several years of continuous full implementation to have an effect and to know if there has been the full effect, you have to see if the child finishes primary schooling, which takes eight years in total. Each school in informal settlements is significantly unique. Assuming that the differences between a school enrolled in the BSI and control group schools over a several year periods are caused by the BSI implementation might not be valid.

With the continued growth of both informal settlements and informal schools, reliable and accurate data will continue to be an obstacle. CFK Africa is aware of these issues. Assistance in overcoming them would be invaluable towards creating valid learning of what can best be done so our children in informal settlements can succeed in obtaining a primary education.

Following this initial phase, the BSI will expand the implementation of the successful best practices, continue monitoring and evaluation efforts, and eventually partner with governments and larger non-governmental organizations to scale the BSI model throughout Kibera and additional informal settlements.

Given the complexities of informal settlements, poor data collection in informal schools, the transient nature of people living in informal settlements, and a multitude of other challenges, we do not have reliable evidence to measure the BSI’s impact. The only direct indicator of the BSI's success in achieving many more children completing primary school is comparing the number of students completing class 8 in the BSI schools to the non-BSI schools. Some of the difficulties we face in measuring this are a number of the BSI schools closed, a few schools that offered class 8 classes discontinued those classes during the project, and numerous students left the BSI school to attend another school, with no record of what school they then enrolled in. Additionally, not enough time has passed from the beginning of a school's implementing of the BSI practice to see its effect on students completing class 8. We try to obtain data over multiple years for how many students enroll in class 8 at the beginning of the year and how many are still enrolled at the end of the year, but this is an insufficient indicator.

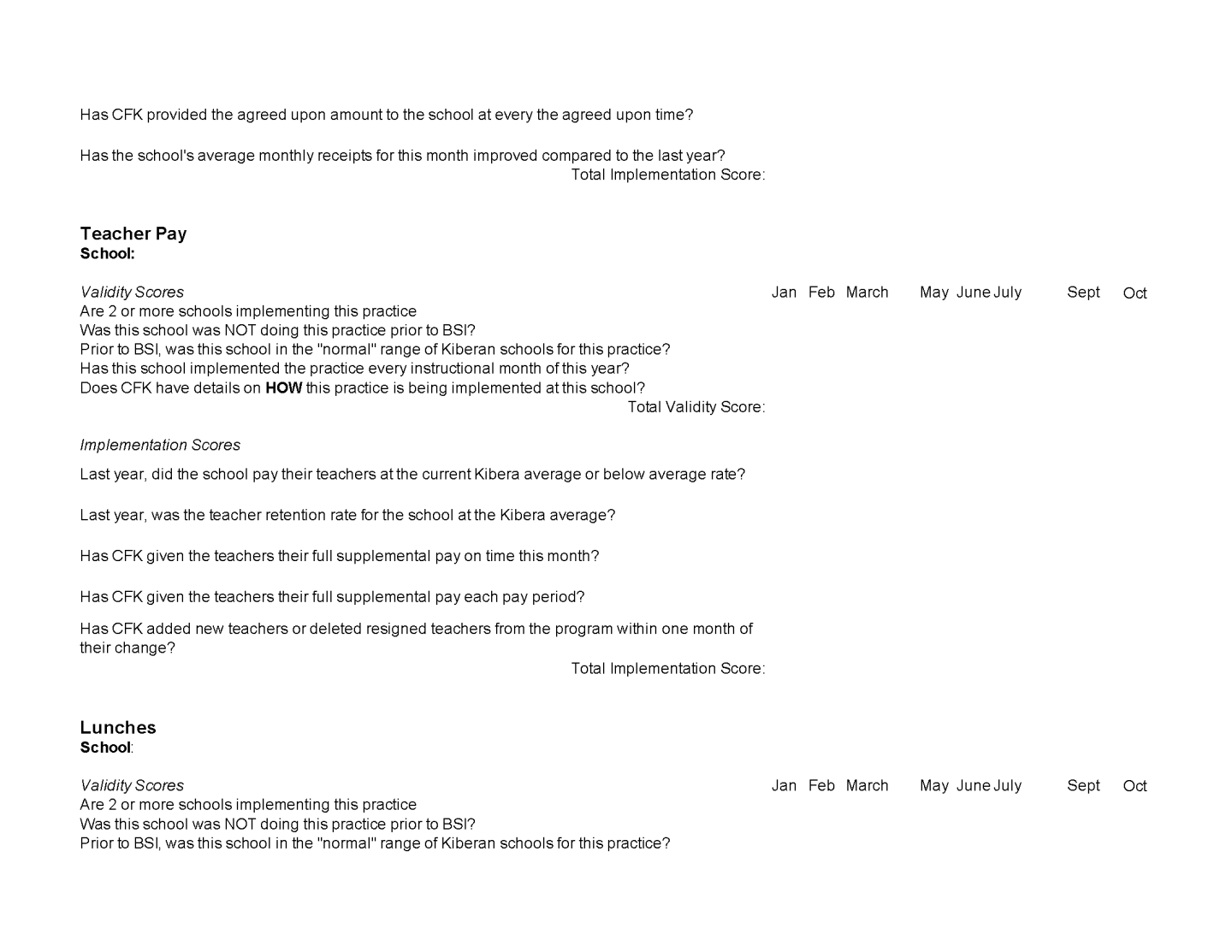

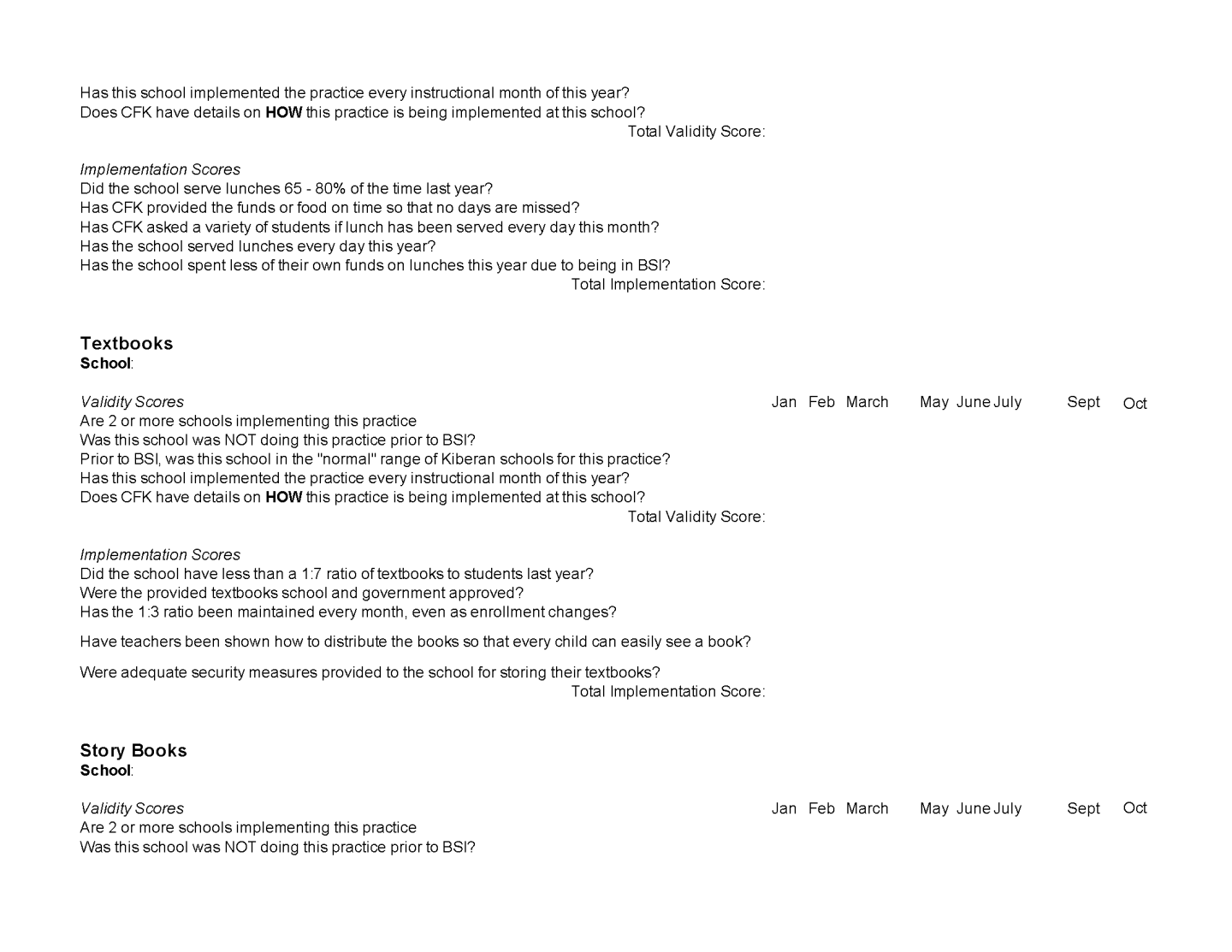

Despite these difficulties, there are outcomes we believe lead to the impact that we are better able to measure. These are student attendance records and implementation indicators. We believe that the level of implementation should have an effect on attendance and, over time, successful completion of primary school. As overall student attendance improves at each grade level, it is reasonable that this will result in more students completing their primary schooling over time. We have developed indicators of the extent to which each practice is being implemented in a school. These are checked at least quarterly, sometimes more often. Our implementation indicators for each practice are included below. Preliminary data suggests that at least seven best practices impacted student attendance and performance. These best practices included affordable school fees, attendance rewards, reliable school lunches, reasonable teacher pay, supplemental reading libraries, teacher training, and textbook-to-student ratios.

CFK Africa’s Best Schools Initiative addresses key structural challenges in informal settlements to improve educational outcomes for underserved students.

- Pilot

Millions of children worldwide are out of school, and millions more are attending informal schools, which vary in quality. In Kenya, there may be as many as 2.6 million students in informal schools. These schools serve an essential role in providing some level of education to the millions of children living in informal settlements, where access to government or philanthropic private schools is very limited or cost-prohibitive. As a result, few of their students are completing primary school. If the Best Schools Initiative can provide strong evidence about cost-effective, best practices schools can adopt to help their students complete primary school, that evidence would transform schools and student lives worldwide.

While the evidence would be transformative, we have found that given the complex environment of informal settlements and informal schools, accurate, reliable data is challenging to obtain. The LEAP fellows would be an invaluable resource to help us strengthen this program, allowing us to impact children worldwide.

Specifically, the LEAP Fellows could help us answer the following questions:

1. What's the best way to get multi-year student attendance and learning data in an environment where attendance and learning records are currently poorly maintained, students change schools frequently, and school leadership and teacher turnover is high?

2. What level of evidence is necessary to judge which practices are most effective?

3. How can causation be reasonably inferred when the number of variables to student attendance and learning is so large?

By the end of the LEAP sprint, we would hope to have

• A solid research framework with reasonable expectations of what data is necessary in what timeframe

• A small group of research experts is willing to give us ongoing advice

as we encounter the inevitable new challenge inherent in working in the rapidly changing environment of education in informal settlements.

Participation in the MIT LEAP project will provide guidance and expertise to support CFK Africa’s the Best Schools Initiative, improving outcomes for underserved students in Kenya’s informal settlement by addressing structural challenges facing informal schools. As CFK Africa becomes, one of the leading NGOs in the education and health space in Kenya, strengthening the research skills capacity of key staff members is a priority of the organization. The MIT LEAP project will increase the organization’s ability to gather and analyze data to inform program interventions across all focus areas within the organization’s strategic plan.

This year, CFK Africa launched a five-year strategic plan to guide programmatic growth and expansion throughout Kenya. For 20 years, CFK Africa has proudly partnered with and served the informal settlement of Kibera, providing affordable and reliable primary health care services and long-term youth leadership and education development.

The development of CFK Africa’s Strategic Plan covering 2022-2026 followed a participatory process in which many stakeholders took part. The plan builds upon CFK Africa’s strong community-based public health foundation by positioning the organization for continued success within Kenya and the African region.

Youth development has been a part of our organization since its founding. When CFK Africa was founded in 2001, one of the main goals was to prevent ethnic violence among youth by engaging them in team-based sports that promoted tolerance, diversity, and leadership. Collaborating with youth leaders remains key to the public health and education work we lead in informal settlements.

CFK Africa was founded on the idea that talent is universal, but opportunity is not. Our Education and Livelihoods programming is changing that narrative. The program utilizes complementary interventions such as school improvement efforts, skill development training, and scholarships to invest in the potential of young leaders living in informal settlements. CFK Africa’s scholarships go beyond financial assistance providing mentorship and safe space programs, leadership training, and career guidance for youth attending high school, vocational school, college, or university. We strive to equip young leaders with the tools needed to lift themselves out of poverty while remaining connected to and serving the communities they came from.

As the growth of informal settlements increases worldwide, evidence-based data gathered from community-based participatory research activities from CFK Africa’s unique platform could lead to pivotal findings applicable to community education and health decision-making globally.